← Back to Blog

A Recursive Decent into Text Adventures

As a challenge, I am trying to write source code for a large number of 3.5” floppy disks. As of today, I completed my second floppy. It is a text adventure. You can find the sources here. The game is also listed on the Floppy Challenge website if you just want the binaries.

I’m sad to say that I never got to play a text adventure as a kid. I was of the Freddy Fish generation: colourful graphics and simple buttons clearly explaining to me what is happening and what I am able to do. It was only in my early teens that I learned about one of the first text adventures, Zork. You can play Zork online these days. The game loop is described in three easy steps:

I’m sad to say that I never got to play a text adventure as a kid. I was of the Freddy Fish generation: colourful graphics and simple buttons clearly explaining to me what is happening and what I am able to do. It was only in my early teens that I learned about one of the first text adventures, Zork. You can play Zork online these days. The game loop is described in three easy steps:

- Game provides introduction.

- User provides commands.

- Game describes results of commands.

- If the results are not a win-state, go to step 2.

- Game provides congratulations.

Of course, there is an argument to be made that most (if not all) games can be reduced to this description. For text-adventures though, this description is extremely close to the actual implementation and behaviour of the game (see the GIF below).

Due to this clear structure, these are very fun to program in imperative languages like C, the language I’ve been using for my floppies up till now. The most important part to implement is the parser. The parser allows for translating the provided human-readable command (step 2 of our game loop) into commands the computer is able to understand. A very simple 1-word parser is easy to make: a mapping between words and actions (think of a large ugly switch case). If the user says north the in-game character is moved north, and if the user says kill the closest enemy is killed. The problem becomes more difficult if we which for our user to write full-blown sentences. Suddenly we do not only need to parse entire statements like kill the goblin with the shortbread, we need to provide hints like the goblin you are trying to kill is not in this room. How do we turn long statements with syntactic rules into actionable statements our code is able to, well, parse?

If this sounds familiar, then that’s because this is exactly the (very simplified) idea behind the very language we are programming our game with! We write C in simple human readable statements, which are parsed and (eventually) get converted into actionable machine code. If an erroneous statement has been provided in C, the compiler will usually give a pretty good hint of what went wrong. I first learned about the topic of implementing parsers by following an university course on Compiler Construction. We will not use tools such as yacc or bison here though, we will roll our own cute little recursive descent parser.

Defining the grammar

In order to write something that can parse a human-readable language, we first need to determine the grammar of the language. Grammars like these are usually defined in Backus–Naur form, with statements in the shape of STATEMENT => DEFINITION. In turn, a DEFINITION can itself have its own SUB_DEFINITION’s or recursively define itself with its own definition. I’m aware that my explanation might be a little bit sub-par, but I’m hoping our text adventure’s grammar definition below makes this idea a bit more clear to you.

STATEMENT := ACTION | MOVEMENT | EXIT

ACTION := INSPECTING | TAKING | PLACING | LOCKING | UNLOCKING | KILLING

INSPECTING := LOOK {AT} ITEM | ROOM | INVENTORY

TAKING := TAKE ITEM

PLACING := PLACE ITEM

LOCKING := LOCK DOOR WITH ITEM

UNLOCKING := UNLOCK DOOR WITH ITEM

DOOR := [a-Z]+

KILLING := KILL ENTITY WITH ITEM

ENTITY := [a-Z]+

ITEM := [a-Z]+

MOVEMENT := WALK DIRECTION

DIRECTION := north | east | south | westThe topmost definition shows the three main things a user can do in this game: an action (walking, taking, placing, locking, unlocking and killing), a movement and exit. The keen reader might notice that this grammar represent a graph of possible commands, with STATEMENT at the root and things like ENTITY and ITEM as the leaves.

This idea of a graph is a very useful mental model to have, as we can now give meaning to each path in our tree, from root to leaf. As long as the user provides a sequence of characters that allow us to traverse the tree, the user wrote a correct statement! If not, we have a pretty good idea of where we diverted from our tree and what kind of feedback to give.

How to write recursive decent parsers

You might be tempted to start writing your string-parsing code immediately, but hold your horses! Good code makes use of abstraction, and the first layer of abstraction we should be writing is concerned with tokenizing our user input. A Token can be described using the struct below.

typedef struct

{

TokenType type;

const char * value;

} Token;Where every Token has a TokenType, which is an enum describing the kind of token we are dealing with, and a value containing any additional information potentially associated with the token. For example we might have a token of type TAKE and an empty value, followed by a token of type ITEM, with a value containing “shortbread”. We can simply be concerned with the types of our tokens and the values they contain, and little to none of the parsing code will have to be rewritten if we translate our entire game to another language! So, how do we write a Tokenizer?

Writing a tokenizer

Writing a tokenizer becomes really easy once you’ve done it once or twice (which is the reason we have programs that write this code for you). We create a loop which iterates until all input has been processed, and within this loop we repeatedly try to match the current unprocessed part of our input with one of the token types we defined. If none of our tokens match, we either ignore the input (allowing you to say things like Take the shortbread already! without already being a known token) or we raise an error (such as when tokenizing a C source file). This process can be summarized with a little piece of C pseudo-code:

while (index < input_size)

{

Token token;

if (acceptToken(TAKE, input, &token, &index))

addToken(&tokenList, token);

else if (acceptToken(WALK, input, &token, &index))

addToken(&tokenList, token);

.

.

.

if (acceptToken(ITEM), input, &token, &index)

addToken(&tokenList, token);

else // No token was matched, try to simply skip a character.

index++;

}

return tokenList;This will result in a neat language-agnostic list of Tokens, ready to be parsed by our Parser.

Writing a parser

Finally, the juicy part. The actual parser is actually not much work to create once you’ve set everything up. Parsing our Tokens and performing in-game actions as a result actually follows a very similar structure as to our above tokenizer: we step trough our tokens and try to match full grammatically correct STATEMENTs. If we partially match a statement and suddenly obtain an unexpected token, we can easily tell the user what information we are missing. If we match a complete statement (a correct sequence of tokens) we have all the information we need and can perform the correct action accordingly! As an example, here is an excerpt from the Text Adventure Floppy:

bool accept_action(TokenList token_list, unsigned * token_index, GameState * game)

{

if (accept_inspecting(token_list, token_index, game) ||

accept_taking(token_list, token_index, game) ||

accept_placing(token_list, token_index, game) ||

accept_locking(token_list, token_index, game) ||

accept_unlocking(token_list, token_index, game) ||

(token_list, token_index, game))

return true;

return false;

}It checks whether the token_list contains an action at the current token_index, and does so by trying to accept the possible sub-statements that can define an action. For instance, taking an item from a room.

bool accept_taking(TokenList token_list, unsigned * token_index, GameState * game)

{

if (accept_token(token_list, token_index, TAKE))

{

if (accept_token(token_list, token_index, ITEM))

{

ItemID item_id = token_list.tokens[*token_index-1].value;

if (is_item_in_room(game->rooms[game->current_room], item_id))

{

Item item = game->items[item_id];

put_color_text(GREEN, "You pick up the %s and put it in your pocket.\n", item.name);

add_item_to_player(&game->player, item_id);

remove_item_from_room(&game->rooms[game->current_room], item_id);

return true;

}

}

put_text("You grasp in thin air... that item is not in the room.\n");

return true;

}

return false;

}Here you can also see what happens when a statement is grammatically correct, but still does not make sense in the current world. We check if the referenced item exists within the room (let’s ignore the fact that our implementation uses Item ID’s instead of strings, see the code on how that’s done), and if it does not exist we simply tell the user and do nothing.

To conclude, parsing more than one or two words does not need to be difficult. Parsing entire grammars does not need to be difficult. Although you can spend years building a highly interactive dialogue system (see this neat video on Facade), a short and simple recursive decent parser will usually do.

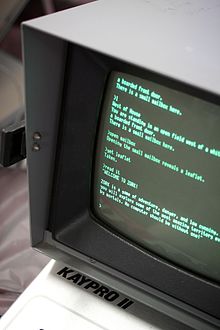

As a short example of my own little recursive-decent parser, I made a quick recording of the first few moments of the game. Watch it below, or play the game yourselves by following the aforementioned link. Thanks to the cool-retro-term for allowing me to play the game on a neat retro terminal!